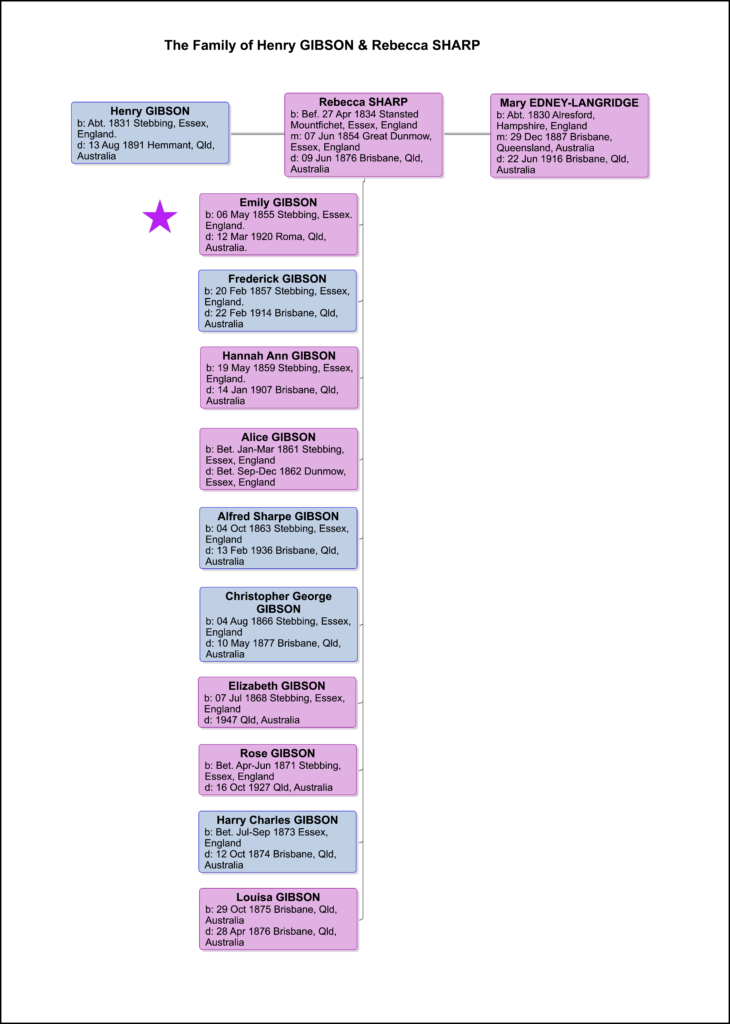

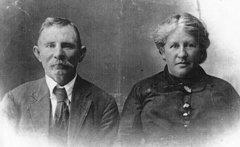

The Grand-Parents of Sarah Rebecca Mary MURRAY

The Essex Connection

Henry Gibson

Henry Gibson was born about 1831, the son of Joseph Gibson and Mary Dale. Their story can be found here. Henry was baptised with his older brother William under the name “Gipson” on 22 May, 1831 at St Mary the Virgin Church in Stebbing. His father Joseph was listed as a labourer on his baptism entry.

Stebbing was a typical rural village during the 1840’s with trades such as cooper and turner, saddler, cattle dealer, baker, thatcher, miller, maltster, brick maker and here’s and interesting one – marine store dealer. There were Inns and Taverns, Beerhouses, blacksmiths, boot and shoemakers, bricklayers and butchers, tailors, wheelwrights and carriers. There was also a National and a British School, on of which Henry probably attended.2

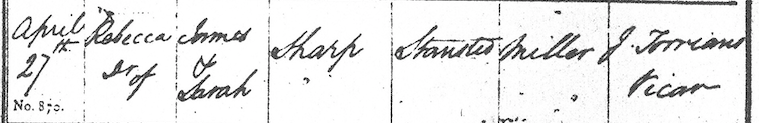

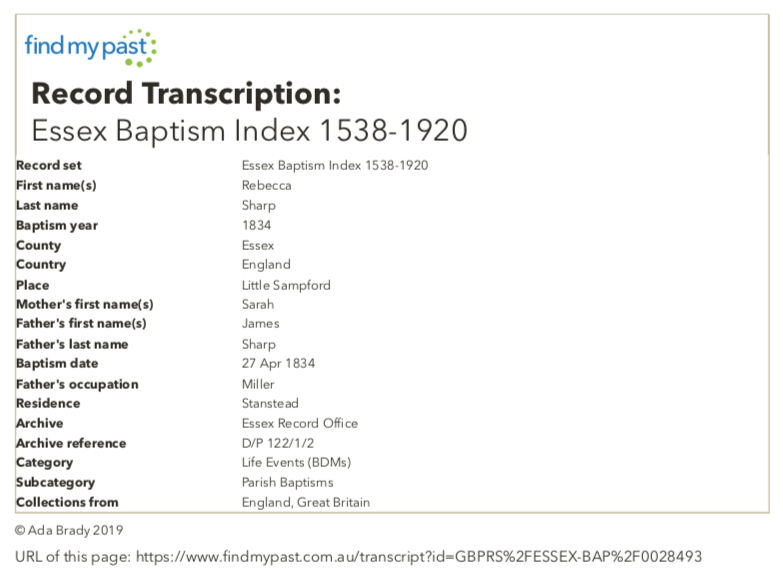

Rebecca Sharp

Rebecca Gibson was born before 27 April, 1834 to James Sharp and Sarah Chalk. There story can be found here.

There is some confusion about Rebecca’s baptism. We have two baptism records for her both on the same day. The first one I found was in the parish record for the Church of England of Stansted Mountfitchet at St Mary The Virgin where she was baptised on 27 April, 1834. An excerpt from this is below.

The other record is a transcript from the Essex Baptism Index 1538-1920, held at the Essex record Office. This shows Rebecca being baptised on the same day but at Little Sampford which is near to Stansted Mountfitchet. This document also says the residence is at Stansted.

So, not only do we have two baptism records for Rebecca but why was she baptised in the Church of England. Rebecca had eight siblings: Elizabeth (b1812), Louisa (b1814), Harriett (b1817), Mary (b1819), Alfred (b1827), Hannah (b1830), James (b1832) and Frederick (b1836) – the ‘b’ in brackets stands for baptised not born in this case.

From the records I could find, it seems the four oldest girls were baptised in the Church of England. Then we have Alfred, the first son and Frederick , the youngest son, being baptised in the Non-Conformist church in Stansted Mountfitchet. I thought perhaps the girls were baptised in the Church of England and the boys in Non-Conformist church but this does not hold true as three of the children Hannah, James and our Rebecca were baptised in Little Sampford Church of England. These other two, Hannah and James also were listed in the Stansted Mountfitchet parish records like Rebecca so have two baptism records. I thought that perhaps they were born here in Little Sampford as it had two mills in the 1830’s and their father was a miller and was living here, but the baptism records both say the place of residence was Stansted.

Perhaps the Stansted Mountfitchet record was an overall record for the whole parish and Little Sampford came under that umbrella but it still doesn’t explain why the next child and youngest son Frederick was baptised in the Non-Conformist church being born in Stansted like his older siblings. One point of interest was both James and Sarah Sharp signed their names on the Non-conformists baptism records for both Alfred and Frederick.

The Non-Conformist church or ‘Non-Conformists’ were Protestants who did not ‘conform’ to the governance and usages of the established Church of England. During the 19th century, the term specifically included the reformed christians (Presbyterians, congregationalists and other Calvinists sects), plus the Baptists, Methodists, Roman Catholics, Quakers and Jews.3

By 1841, Rebecca , aged seven, was living with her parents and siblings in Matching, Essex. Matching was about 10 kilometres south of Stansted. Her father was the miller at Down Hall Mill. Rebecca’s childhood would have been slightly different from many of her peers. With her father being a miller, she moved from town to town with his work. Just from what I can gather from their story, Rebecca would have been in Stansted, High Easter, Matching and perhaps other towns before ending in Stebbing before 1854.

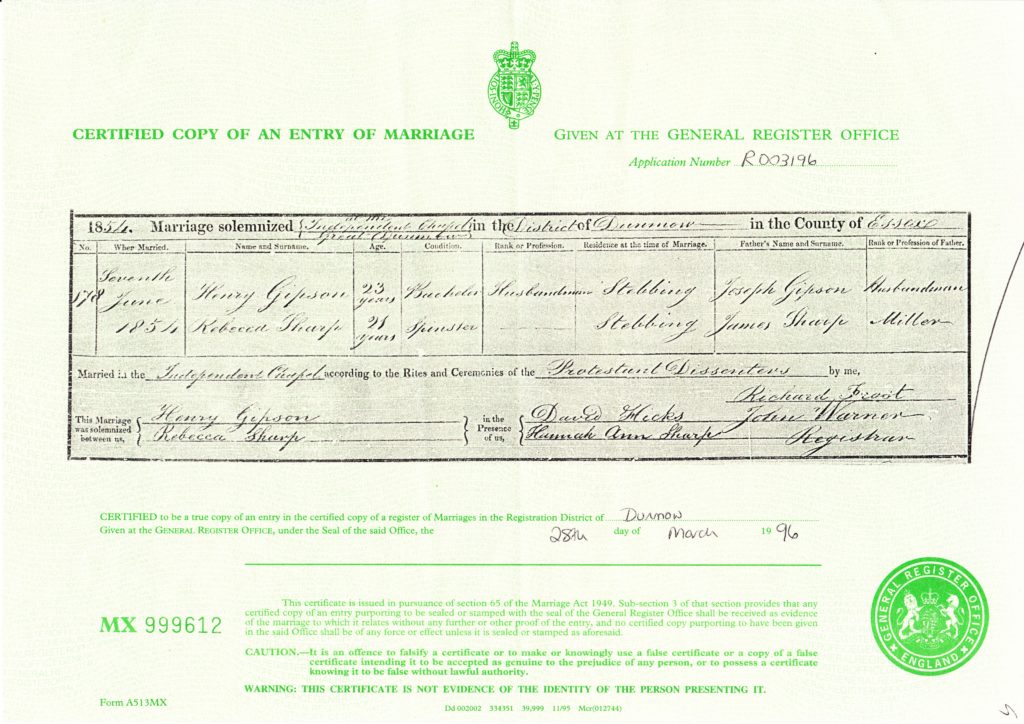

Marriage

Even though Henry Gibson was baptised in the parish church in Stebbing, he married Rebecca Sharp on the 7 June, 1854 in the Independent Chapel at Great Dunmow. It seems the influence of the Sharp family being protestant Dissenters persuaded Henry to marry in this church. Also of interest, Henry was married under the name of ‘Gipson’ – obviously a mispronounciation of Gibson.

The Gibson family stayed in Stebbing for the next 20 years with Henry working in the area as a labourer and Rebecca raising their family. Henry and Rebecca had nine children, six of which survived childhood. There were Emily, Frederick, Hannah Ann, Alice, Alfred, George, Elizabeth, Rose, and Harry or Henry.

A little history:

“In medieval times farming was based on large fields, known as open fields, in which individual yeomen or tenant farmers cultivated scattered strip of land. From as early as the 12th Century, however, agricultural land was enclosed. This meant that holdings were consolidated into individually-owned or rented fields. Originally, enclosures of land took place through informal agreements. But during the 17th century the practice developed of obtaining authorisation by the Act of Parliament. Initiatives to enclose came either from landowners hoping to maximise rental from their estates, or from tenant farmers anxious to improve farms.

From the 1750’s enclosure by parliamentary Act became the norm. There is little doubt that enclosure greatly improved the agricultural productivity of farms from the late 18th century by bringing more land into effective agricultural use. It also brought considerable change to the local landscape.

Where there were once large, communal open fields, land was now hedged and fenced off, and old boundaries disappeared. But Historians remain divided over the extent to which enclosure forced those at the lowest end of rural society, the agricultural labourers, to live the land permanently to seek work in the towns.”4

The last Enclosures Act was in 1867 and perhaps this affected Henry and his ability to feed his family. ‘It deprived the rural labourer of the opportunity to exercise peasant thrift by putting a fence around the acres over which his cow, donkey, geese, fowls, or swine used to graze and from which he derived fuel for his household, fodder for his beasts and even corn for his daily bread. He had little else to sell but his labour, and the labour of his family. It was difficult to see what course was open to him as a voteless, voiceless man, if the farmers refused to meet him, but to strike.

Even though the Land Commissioners had instructions to reserve sufficient Common Land for the needs of the rural poor, very little was assigned to them. It must have rankled the labourers, that so many acres had been enclosed, not to grow corn, but to make parks and shooting preserves for a new class of landed plutocracy.5

Perhaps it was this loss of common land and work and the promise of a new and prosperous life in Queensland that induced Henry and Rebecca Gibson and family to leave England. With the exception of one child Alice, who died in 1862, the family sailed on the ‘Zoroaster’ on 3rd June 1874 for a three month journey to Moreton Bay arriving on 8 September. The family was Henry (43), Rebecca (40),Emily (18), Frederick (17), Hannah (14), Alfred (11), George (8), Elizabeth (5), Rose (3) and Henry (1). A copy of the Ships Log with the family listed can be found here.

Immigration

There was an article written about the departure of the ‘Zoroaster’ in the People’s Courier – a periodical of the Labourers’ Union in Britain. It was reproduced in The Queenslander on Saturday 26 September, 1874. The Queenslander was the weekly summer and literary edition of the Brisbane Courier (now The Courier Mail):

The Zoroaster – Embarkation

After a tedious voyage of 107 days from London, the ship Zoroaster, with immigrants entered Moreton Bay on Wednesday. From the ‘People’s Courier‘ (an organ of the Labourers’ Union, and edited by Mr. Richardson) we take the following notice of the vessel’ departure:-

“On the morning of Friday, May 29, this fine vessel of 1207 tons register (Messrs. Taylor, Bethell, and Roberts, 110 Fenchurch-Street) was ready to receive the 400 emigrants who had secured free and assisted passages inter to Brisbane, Queensland. The emigrants arrived early, and in great batches, mostly from Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Hampshire, and Cambridgeshire. A large proportion of the labourers were Unionists and wone the ribbon. The principal local agents came up with the parties by special arrangement with the various railway authorities, and lent valuable assistance to those who had never seen a ship before, in berthing themselves and securing their ship-kit and luggage. The allowance for the emigrants’ luggage must be on a liberal scale, for one man brought something like a house in four moderate sized packages, each about six feet by four. By supper time the Zoroaster was considered full – one family too many, each berth for single women occupied, and only two or three vacancies for single men.By 9 o’cock p.m. there was nothing to hear or see beyond a quiet promenading of the passengers on deck or by the rive side.

The following morning the London relatives come down to say farewell. One family party of brothers, sisters, aunts, cousins and the like, in all some twenty person from the little village of Holton, near Oxford – where the head of the family had worked on one estate for thirty years – were chatting gaily in a group by the ship’s side, and were, as they said, only going to join some one who had gone out before. Where the treasure is, there will the heart be also. The poop was taken up by single girls, who were, in many instances, scribbling a hasty note for the next post. The Zoroaster is the 137th vessel that sails under the Land-order System of emigration, and is expected to leave Gravesend early on Thursday morning. Captain, Samuel Wakeman; Surgeon-superintendent, Dr, Hickling; Matron, Mrs Margaret Willes. The single girls are fortunate in having an experienced and conscientious person like Mrs Willes to look after the general welfare.”

There was also an article in the Brisbane Courier about the voyage of the ‘Zoroaster’ in the Wednesday edition of 30 September, 1874. I will interpret it as follows:

The Zoroaster – Voyage

“The Zoroaster of the London Line, with Captain Wakeman and immigrants, left Gravesend, Thames River on June 3, 1864. The pilot who guided the Zoroaster’ out of the Thames and down the east coast of England was landed at Start Point, Devon – on the south-east tip of coastline, on June 6. The ship passed the Lizard in Cornwall, the most southerly tip of England, the following day and had a fine run out of the English Channel, and met with moderate north-east trade-winds. The Zoroaster crossed the Equator, 29 days out, in longtitude 28°W., and the south-east trades proved steady as far as latitude 30°36’S., and longitude 29°56’W. (This was in a south-westerly direction leading towards South America virtually tow-thirds of the way across the Atlantic Ocean before turning towards South Africa). The ship then turned and followed the meridian of the Cape of Good Hope, which was passed on August 4. they had strong winds followed by moderate winds and fine water while running down the easting. (Running down the easting was a common expression among seamen and related to ships leaving England travelling down the Atlantic Ocean and around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, picking up the the predominately westerly winds – Roaring Forties – for a fast easterly trip across the bottom of the Indian Ocean until reaching Tasmania where they could turn north or continue to New Zealand). The ship experienced a succession of gales from Cape Leeuwin on the most southerly tip of Western Australia to the Tasmanian coast, rounding the South West Cape on September 7. Light variable winds delayed the progress of the vessel up the coast of Australia, and Cape Moreton, Queensland, was rounded on September 22, after a fine and pleasant passage throughout.”

Another article appearing in Wednesday 30 September, 1874 Edition of the Brisbane Courier listed the cargo ‘Imports’ arriving on the ‘Zoroaster’.

Zoroaster – Imports

‘Zoroaster’, ship, from London: 300 cases bottled stout, 200 cases bottled ale, 300 cases schnapps, 400 hogsheads ale, 20 quarter-casks wine, 21 quarter-casks brandy, 275 cases brandy, 630 cases claret, 32 cases champagne, 30 cases curacoa, 2 casks gin, 100 run hogsheads, 6 tanks hops, 200 casks cement, 200 bundles fencing wire, 20 cases galvanised iron, 172 plates 120 bars 240 sheets iron, 147 packages and pieces machinery, 94 lengths pipes, 16 cases hardware, 7 casks rivets, 7 kegs nails, 255 packages iron goods, 47 bundles iron tubes, 16 bundles galvanised buckets and tubs, 9 wheels, 8 anvils, 5 packages earthenware, 6 bales canvas, 33 packages apothecaries’ ware, 2 cases perfumery, 12 cases books and stationery, 3 cases concertinas, 2 cases pianos, 100 boxes candles, 10 kegs pearl barley, 6 cases groats, 20 cases mustard, 8 cases cocoa, 25 cases sauces, 5 casks blacking, 5 casks caraways, 10 cases chicory, 20 boxes corn flour, 19 packages corks, 40 tins potatoes, 35 cases pickles, 35 casks currants, 5 packages raisins, 40 boxes starch, 283 packages oilmen’s stores, 22 bales woolpacks, 6 crates bottles, 23 trunks boots, 33 cases hats, 25 cases clothing, 317 packages drapery and hosiery, 1028 packages merchandise not described. For Ipswich: 2 cases straw hats, 5 packages merchandise.

Ex. ‘Zoroaster’: 7 cases books, G. Slater and Co.

Ex. ‘Zoroaster’, from London; 2o cases galvanised iron, 100 cases Knight Bevan’s cement, 80 cases Bass’ quarts ale, 20 cases Bass’ pints ale, 150 cases Red Heart rum, 20 cases condensed milk, 21 quarter-casks Marett’s brandy, 125 cases Marett’s *brandy, 25 cases Marett’s *** brandy, 25 cases flask brandy, 13 cases Hennessy’s *** brandy, 37 cases Hennessy’s *** brandy (dark), 1 case Warde and Payne’s sheepshears, 145 cases claret, 32 cases champagne, H. Box & Son.

For reference: Hogshead = 52.5 imperial gallons or 238.7 litres.

Australia

Also on board the Zoroaster were a family from Hampshire – John and Mary Langridge and their eight children. John was also an agricultural labourer. It is unlikely these two families knew each other before the voyage, however, their lives would be interconnected after arrival in the new colony.

One wonders if Henry and Rebecca ever regretted leaving England to come to Queensland. Perhaps they did, especially Henry, as they lost their young son Harry (Henry) Charles within three weeks of arriving. Rebecca gave birth to their last child Louisa on 20 October, 1875, just over a year after arriving. According to her death certificate Rebecca fell ill in February 1876 with chronic ulceration of the intestines. Several months later, baby Louisa died on 28 April, possibly because she couldn’t get sustenance from her ill mother. Rebecca was admitted to hospital on 8 May suffering with diarrhoea on the recommendation of Dr. Prentice. Rebecca died on 9 June, 1876 and was buried at Coopers Plains. She was 43 years of age. And then tragedy struck again when young 10 year old (Christopher) George died in May 1877. George drowned in the Logan River while working for a Mr. James Scott. To lose your wife and three of your young children within 3 years of arriving in a foreign land would, no doubt, have been quite devastating.

The Gibson family obviously kept in touch with the Langridge family as Hannah Ann Gibson married Frederick Langridge in 1881. And in 1887, eleven years after Rebecca’s death, Henry married Mary Langridge. Mary’s husband John had died in February 1876, the same year as Rebecca. Mary had her own sorrows, not only losing her husband but also her young daughter Emily within two years of arriving in Queensland.

Henry had settled and farmed in the Yeerongpilly area of Brisbane and was listed on the 1886 Bulimba electoral roll as having a residence there. He and Mary would have probably had some of their combined family with them, 14 children in all, still living with them as the youngest Rose, was 17 years old. Henry and Mary moved from their Yeerongpilly property to Hemmant sometime before 1891.

Henry and Mary had a very short marriage as on 12 August 1891, at the age of 61 years, Henry was hit on the base of his skull by a falling limb from a tree. He suffered a fractured and died 20 hours later on 13 August. Henry was buried at the Bulimba Cemetery. Interred in the same plot at the cemetery are his son Frederick, Frederick’s second wife Elizabeth Fallon, and Frederick’s children Frederick and Winifred.

Mary died on 22 June, 1916 and was buried at the Nundah Cemetery.

Children

Frederick, the eldest living son, married Alice Elizabeth Holpen in 1880.6 Fred and Alice were married in the Wesleyan parsonage, and Frederick had a dairy farm in Kianawah Road, Hemmant.7 It was here that his wife Alice died tragically at the early age of 38 years from burns to the whole of her body and subsequent shock. It is believed that her clothes caught fire as she was tending a boiling copper whilst doing the washing. At this time, women were still wearing long ankle-length dresses with long petticoats. After Alice’s death, Fred moved into Wynnum and became a storekeeper8 and insurance agent.9 Fred and Alice had six children.

Fred married again in 1901 to Elizabeth Fallon. They had three children together.

In 1902, Fred became the first Chairman of the Wynnum Shire Council. He was then a storekeeper, living in King Street (now Glenoa Street, Wynnum).

Fred died in 1914 leaving Elizabeth with her three young children and possibly a step-daughter. As mentioned above, in his parents story, Fred was buried in the family plot with his father Henry, wife Elizabeth, eldest son Frederick and daughter Winifred.

His wife, Elizabeth died in 1935.

(Compliments of Val Hanlon – descendant of Henry and Rebecca Sharpe.)

Emily married James Murray and their story can be found here.

As mentioned before, Hannah Ann married Frederick Langridge, also a farmer, whom she had met on the ship coming to Queensland, and they had seven male children, of whom only two survived infancy.

(Compliments of Val Hanlon – descendant of Henry and Rebecca Gibson and also a descendant of one of the surviving male children on Hannah and Fred)

Hannah died in 1907 and Fred died in 1933.

Alice did not survive infancy, dying at the age of about two in 1862 back in Essex before the family had sailed from England.

World War l

Alfred, who never married, worked as a stockman.

At the age of 52 years he falsified his age and enlisted in the Army and served for a short time in WW1, although he did not go overseas. Alfred also enlisted under the name of Alfred Samuel Gibson not Alfred Sharpe Gibson. His sister Rose Wright is listed as his next of kin.10

After the war, he seemed to become a loner. Alfred died in 1936 and is buried in the Esk cemetery.11

(Compliments of Val Hanlon – descendant of Henry & Rebecca Sharpe)

If you have any more information,

Could you please contact me so I can add to this story.

Daughter Rose (b.1871), was only 5 years old when her mother died in 1876, so she was probably mostly raised by her older sisters Emily and Hannah. Her father remarried in 1887. Rose bore a son, Herbert Charles Gibson in December 1889 but he died in March 1890.[efn-note]Qld Births, Deaths & Marriages. Reg. No. B022849. Page 9250.[/efn_note] Many believe he was the son of her future husband whose first name was Herbert as well.

Rose married Herbert Philip Essex (Jack) Wright in St Philip’s Church of England, Thompson Estate (Annerley), Brisbane on 28 April, 1891.[enf_note]Marriage Certificate of Rose Gibson and Herbert P.E. Wright 28 April 1891[/efn_note] Their first child, Olivia was born in June of that year.

According to “A Place in History – The Wright Story” by Donna Fraser, early in their marriage they moved with their infant daughter to the Caboolture district where Jack worked as a house painter. Jack is remembered for a great sense of humour, famous for his saying “My name is Herbert Philip Essex, but I don’t use the Essex much these days – I’ve got a Ford.”

Rose and Jack later moved to Greenmount, near Toowoomba, and then to Roma where they bought a small dairy farm in the Upper Dargal district 14 miles from Hodgson. Jack named the property ‘Valetta‘ for the place he said his father had lived in Malta before coming to Australia. Possibly they moved to Hodgson as Rose’s eldest sister Emily, was living at there with her husband and family.

It was mentioned that Herbert Wright was the only grower of cotton in the Hodgson area. In 1925, he harvested 627 lbs of cotton from 2½ acres in his first pickings on ‘Valetta’.12

Rose was a loving and caring woman. She kept a family Bible recording the names and birthdates of her 13 children, together with newspaper clippings, notices of death of the three children who predeceased her and the annual In Memorium notices.13

Altogether they had 13 children and lived at’ Valetta‘ until after Rose’s death in 1927, when Jack sold th property and moved to a large block, part of the 400,000 acre Mount Abundance Station which was resumed for closer settlement in 1927. Rose was buried in the Roma Cemetery and her obituary in the Western Star reads: “A very respected resident of this district in the person of Mrs Jack Wright passed away at the Roma Hospital on the morning of 16th October. The deceased was a native of Essex, England and came to Qld about 56 years ago. Some years after her arrival in Queensland she was married to Mr Wright and with her husband, lived at Greenmount, on the Darling Downs, for a short time. The came to the Dargal District where they have lived practically ever since. There are ten surviving children. The eldest, Harry, served with the A.I.F. in France. There are also several grand-children. The Wright family have the sincere sympathy of the local community in their loss.”

Two family stories recalled in “The Wright Story” by Donna Lomas were firstly when the boys took a dray-load of wool to nearby Muckadilla and Jack followed in his car. The boys stopped to rest at a creek crossing and were surprised to see Jack come bumping along the road with one solid tyre having come off the rim and lodged crossways on the wheel. When they pointed this out, he said: “I thought it was running a bit rough!”

Then, some years after Rose’s death Jack met the widowed Belle Thornton who ran the grocery store in Muckadilla, and they were married in 1932. During his courting, his sons’ teased him and made up the following rhyme, “Our father, who art in Muckadilla, Herbert be thy name. Thy Ford is done, thee’ll have some fun to get it goin’ again.”

(Compliments of Val Hanlon – descendant of Henry & Rebecca Gibson)

Jack died in Caboolture on 18 October 1939, aged 63 years, and is buried in the Caboolture cemetery.

If you have any more information,

Could you please contact me so I can add to this story.

- https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2476698/st-mary-the-virgin-churchyard

- White’s Directory of Essex, 1848.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nonconformist

- https://www.parliament.uk/about/livingheritage/transformingsociety/towncountry/landscape/overview/enclosingland/

- ‘A history of the English Agricultural Labourer, 1870-1920’. F. E. Green. http://archive.org/stream/historAyofenglish00greeuoft/historyofenglish00greeuoft_djvu.txt

- Qld. Birth, Death & Marriages. Ref 1880/B007020.

- Death Certificate of Alice Gibson, nee Holpen, 21 November, 1899.

- Qld. Electoral Rolls 1903, Division Oxley, Sub-Division Wynnum

- Death Certificate of Frederick Gibson 1914

- Digitised copy from National Australian Archives- WW1 records

- Death Certificate Alfred Sharp Gibson 13 February 1936

- Western Star & Roma Advertiser. 4 April, 1925.

- Courtesy of Donna Fraser.