The Great-Grandparents of Sarah Rebecca Mary Murray

The Essex Connection

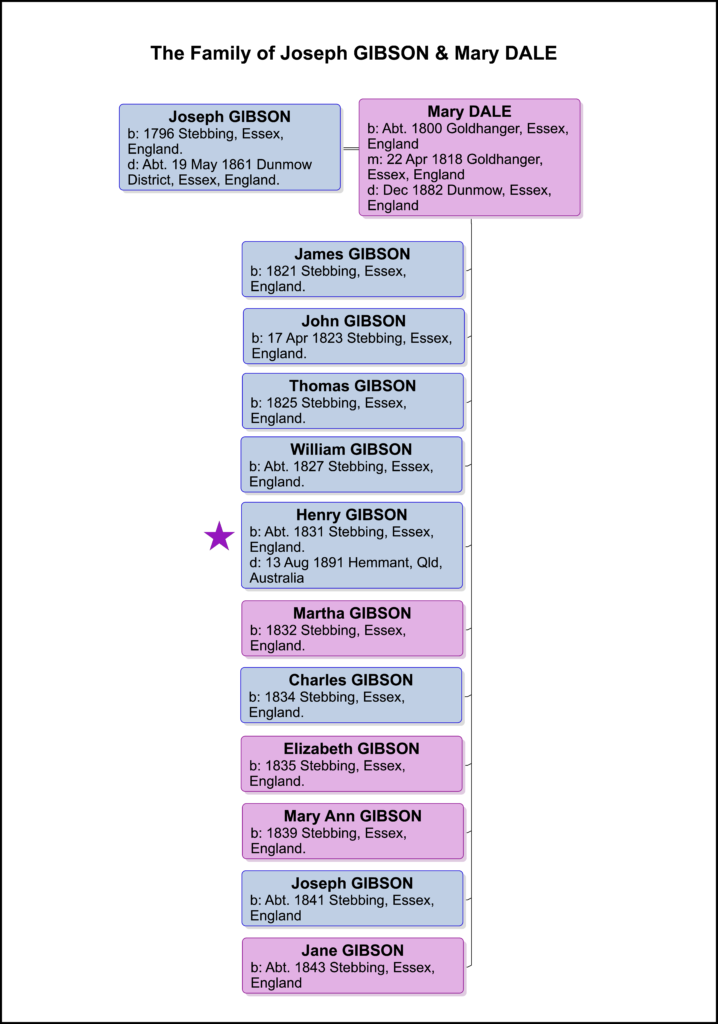

The Gibson family had a long association with the village of Stebbing, at least from 1745 or even earlier.1.

The description of Stebbing was taken from a website ‘The Stebbing Village Page’ which is no longer available:

‘Stebbing lies just north of the Roman Stane Street, one of the main routes to the major settlement of Camulodorum (not Colchester), which is the oldest recorded town in Britain. The High Street with its inns and shops formed the centre of the village. The northern end of the village, where the High street meets the road from Great Dunmow to Great Bardfield, is known as Bran End. At the southern end of the High street lies Church End, not surprisingly a tour of cottages lie around the parish church. In common with many communities in the Eastern counties, the village grew away from the church. Perhaps this had something to do with the rise of Non-Conformists or Dissenters in the area, with the Friends Meeting House and the Chapel being much nearer to the village centre. The Stebbing Brook runs parallel to the High Street and feeds the Water Mills.’

Because Stebbing is so old it contains an unusually wide variety of building styles ranging from medieval half-timbering to 18th century weatherboarding. There are also splendid examples of pargeting – the decorative plasterwork on outside walls. For more information and some photos, please visit Bob Kirby’s website.

Joseph GIBSON

Joseph Gibson was baptised at St Mary the Virgin Church in 4 September, 1796 in the village of Stebbing. He was the youngest of five children to Anthony Gibson and Elizabeth Boreham.

This historic church was built around 1326.4 The earliest written record referring to the present church dates from 1377, when it was reported of Henry de Ferrers that he was ‘said to have been born in the Abbey of Tilty and baptised in the church of St. Mary the Virgin, Stebbing.5

An outstanding feature of St. Mary the Virgin Church is the stone rood screen inside, that divides the chancel from the nave – see right. It is one of only three that survive in Europe.

Mary DALE

Mary Dale was baptised on 6 April 1800 , in St Peter’s Church of England, Goldhanger.7 Her parents were Henry Dale and his wife Sarah. There is a Henry Dale marrying a Sarah Reachey on 26 February 1794 in Goldhanger (this is the only one I could find), so I assume they are her parents.

Marriage

In 1763, the minimum age for marriage was set at 16 years. Previously, the church accepted marriage of girls of 12 years and boys of 14 years. Those under 21 years still needed the consent of parents.

8

Joseph married Mary Dale, a minor on 22 April, 1818 at Goldhanger, Essex. Mary was born about 1800 to Henry Dale and his wife Sarah. Joseph was also listed as a minor on the marriage licence and marriage certificate. Both these documents had to be signed by their fathers, Anthony Gibson and Henry Dale. They went surety of one hundred pounds (a high amount in those days) paid to the bishop, that there was no impediment to the marriage. How Anthony Gibson, a husbandman or farmer, and Henry Dale, a blacksmith, could afford this money is a mystery. Joseph also had to sign an oath that: ‘He knoweth of no lawful Impediment, by Reason of any Precontract, Consanguinity, Affinity, or any other lawful Means whatsoever to hinder the said intended Marriage, and prayed the Licence to solemnise the same in the Parish Church…..’.

Interestingly, Anthony and Joseph Gibson and Mary Dale signed the documents with a mark, but Henry Dale – the blacksmith – signed his name.9

Why Joseph and Mary had to marry before the age of 21 years is a mystery, but perhaps there is an explanation. Mary’s parents had seven children between 1796 and 1808 and then had another two children Elizabeth, born 1816 and Joseph, born 1818. It is not unusual to have a gap of 8 years between children but perhaps these two were the illegitimate children of Joseph and Mary. The name Elizabeth could have been for Joseph’s mother and the Joseph for himself. And again, it is not unusual for illegitimate children to be brought up as the children of the grandparents.

In a Tithe Map from 1839, Joseph and his family were one of three families occupying Plot 449 in Stebbing, which included two residential buildings. One of these buildings still stands to-day and is called Tweed Cottage. Tweed Cottage is a Grade ll historical Listed Building.10

In the 1841 census for Stebbing, Joseph is listed as an agricultural labourer and living with Mary and eight of their eleven children; John (18), Thomas (16), William (14), Henry (12), Martha (10), Charles (8), Elizabeth (6) and Mary (2). Between 1841 and 1861, Joseph continued being a labourer at Stebbing, although there is no census available for 1851 to prove that the family was still there.

One reference I did find in the 1851 census (not in Stebbing) was for second son John, who was in the Essex County Goal and listed as a criminal prisoner. There were 268 Males and 30 females in the goal at the time. It was located in the Springfield parish of Chelmsford.

In 1861 we find Joseph and Mary were living with their two youngest children, Joseph also a labourer and Jane. However, times were tough for Joseph and, no doubt, other labourers in the area. There is a report of a ‘Suicide at Stebbing’ in the Chelmsford Chronicle on 24 May of that year.

‘On Friday, an inquest was held at the White Hart, Stebbing, before C. C. Lewis, Esq., coroner, on the body of Joseph Gibson, labourer, of that parish, who drowned himself on the previous Wednesday. Henry Gibson deposed that he is son of deceased, who was 67 years of age; he last saw him alive about seven o’clock on Wednesday morning; was walking along the footpath in the direction of Stebbing Park farm, and he spoke to him; he said he did not get any better, and went of toward the park; about five minutes after, a boy named Perry came past where witness was at work, and said that a man was in the moat; he went directly, with a man named Tilbrook to the spot; he saw a hat near the moat, and his father in the water; they got him out immediately; he was alive, but insensible and speechless, and died in a few minutes. He had been strange in his mind for some time; he belonged to a club which breaks up every year, and he had half-pay (3s. 6d. per week) from it; he had not done any work since last harvest, and had been in the union a great part of winter; had a dread of going into the union, which preyed upon his mind; he knew that he must go into the house after his club broke up, as, they would not take him into it again. – James Perry, Jane Gibson, and Susan Judd having examined, the Coroner summed up, and the jury returned a verdict of “Temporary insanity”.’

What I believe happened was that Joseph was in a club – probably a labourer’s club, which found work for a group of men. But he was either getting too old or possibly infirm to be given work with it again. The ‘union’ was probably the ‘poor’ workhouse where he had been for a great part of winter and dreaded going back to again.

‘During the medieval period, the care for the poor was a matter for the church, but by the early 17th century, the poor became the responsibility of the parish where they lived. An appointed overseer would administer payments to the parish poor or run a parish workhouse. This system of poor relief was paid for by wealthier residents of the parish by payment of a local tax known as a ‘Poor Rate’. However, in 1834 the Poor Law Amendment Act changed the responsibility for the poor from the parish and amalgamated them into Poor Law Unions with elected Board of Guardians. Admission to a workhouse became the main way of dealing with the poor. A workhouse was run by a master or governor whose task was to supervise the inmates, clothe and feed them and set them to work. As far as possible elderly inmates were expected to undertake the same kind of work as the younger men and women, although concessions were made to their relative frailty. Or they might be required to chop firewood, clean the wards, or carry out other domestic tasks.’11

Joseph was buried on the 19 May, 1861 at Stebbing.

Mary lived for another 20 years. In 1871, Mary, aged 71 years, was still living in Stebbing by herself with no occupation.

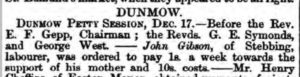

There is a small reference (below) in the Essex Standard of 21 December, 1877 where the second son John Gibson was ordered by the court to pay one shilling a week towards the support of his mother.

But by 1881, Mary is living the Union Street Workhouse in Great Dunmow.

The Dunmow Union workhouse was built between 1838 and 1840 in an Elizabethan Tudor style. The 1881 census tells us that there were 192 pauper inmates in the Great Dunmow workhouse between the ages of two and 92 years. Many would be unable to work through old age but others were unemployed agricultural labourers, shepherds or millers. (For more information on the history and photos of the workhouse see Peter Higginbotham’s web site: www.workhouses.org.uk.)

Being 81 years of age, life in the workhouse for Mary would not have been very nice or easy. There would have been adequate food but the living conditions would have been cramped and the menial work eg. oakum-picking – the teasing out of fibres from old hemp ropes – would have been very painful on fingers and the hours would be long.

Why Mary ended up in the workhouse is not known. I looked for her children from the 1881 census and could only find Joseph, aged 43 years, an agricultural labourer, living with his wife and three children at Little Dunmow, and William aged 51 years, a blacksmith, living with his wife and son aged 18, at Willingale Doe, near Ongar, Essex. Both these places were relatively close to Great Dunmow so I wonder why Mary ended up in the workhouse and not living with either of the sons or possibly the daughters who were no doubt married.

My ancestor Henry had already sailed for Australia in 1874.

Mary died in December, 1882.12

If you have any more information,

Could you please contact me so I can add to this story.

- Parish Register, Stebbing, Essex. 1712-1929 Film#1472761

- www.the-kirbys.org.uk/gen/Places/Stebbing/GenealogyNotes.html

- www.the-kirbys.org.uk/gen/Places/Stebbing/GenealogyNotes.html

- www.smvstebbing.com/

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stebbing.

- www.essexchurches.info/chruchj.asp?p=Stebbing.

- Essex, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Deaths, 1538-1812. Ancestry.com.

- http://www.essexchurches.info/church.aspx?p=Goldhanger

- Marriage licence, certificate and oath of Joseph Gibson and Mary Dale. Courtesy of Val Hanlon.

- https://britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/101112764-tweed-cottage-stebbing#.XYWs8i1L1hE.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Workhouse.

- Births, Deaths Marriages – England & Wales 1837-1983. Volume 4a, Page 298.